Event

March 17, 2026

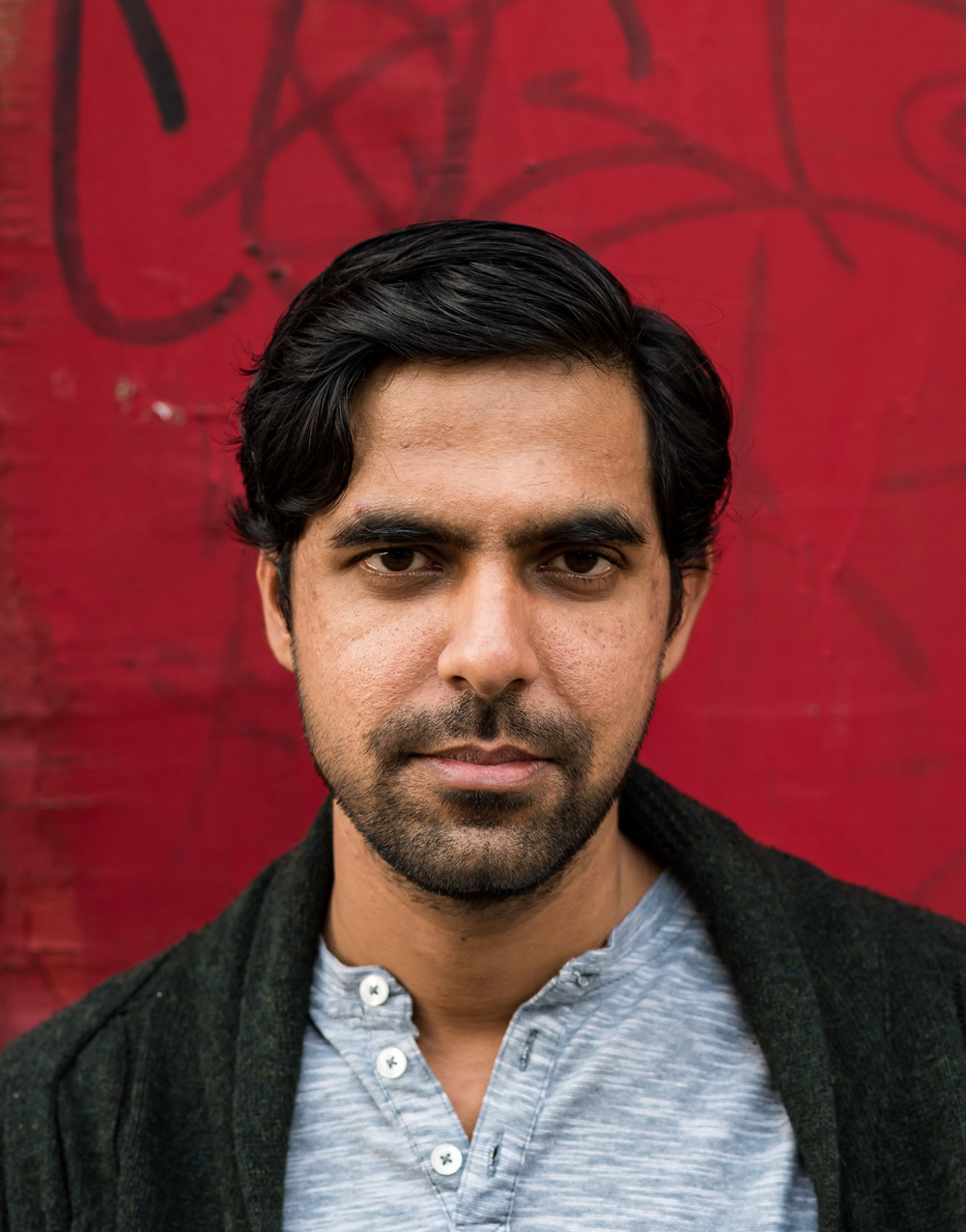

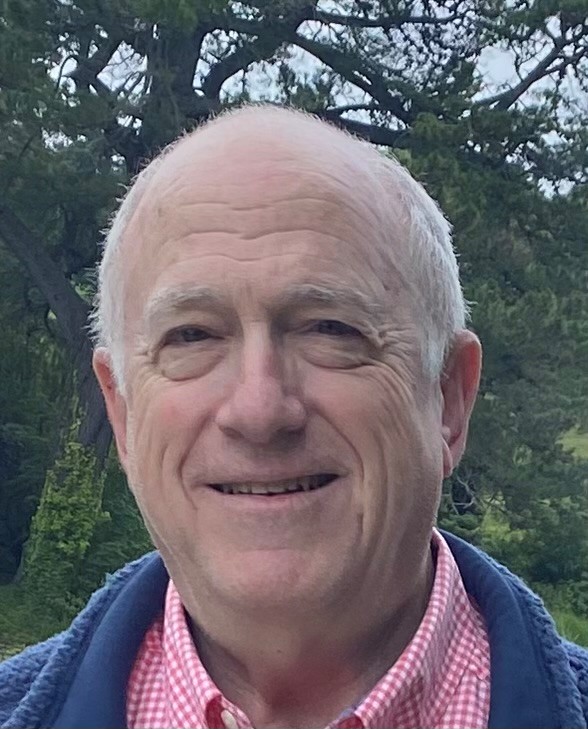

5:00 PM - 7:00 PM EDTMilan Vaishnav, Karan Mahajan

Milan Vaishnav, Karan Mahajan

Aaron David Miller, Yael Lempert, Daniel C. Kurtzer, …

Bama Athreya, Saskia Brechenmacher, Mayra Buvinic, …

Jane Darby Menton, Rose Gottemoeller, Matthew Bunn, …